Pyogenic spondylitis is a life-threatening neurological condition.

Detecting Vertebral Bone Infection

Mold toxicity is a subset of pyogenic spondylitis called vertebral osteomyelitis. This is basically an infection within the bone marrow of vertebrae. Not only does it cause severe pain, if left unchecked it can result in necrosis, vertebral collapse, and further complications.

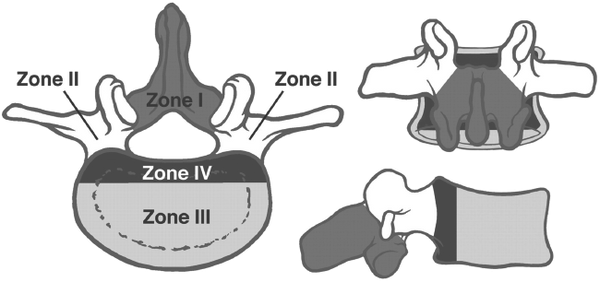

Pyogenic spondylitis is a rare life-threatening neurological condition primarily affecting adults in their fifth decade of life. It encompasses a broad range of clinical entities, including pyogenic spondylodiscitis, septic discitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, and epidural abscess. (Figure 1.)

Osteomyelitis is frequently classified according to the duration of infection as acute (days) or chronic (weeks or months) and the mechanism of infection. Some cases of osteomyelitis last for years. Among dozens of possibilities, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are most common pathogens.

Symptoms of osteomyelitis in the geriatric population are more likely to be subtle or atypical with minimal or absent fever, leukocytosis, and signs of local inflammation. Though weight loss is more common, unintentional weight gain has been reported particularly among the elderly (50-59: 42.86%) in a small sampling.

Bacterial intruders can travel from other parts of the body, such as the ear, throat, or intestines, through the bloodstream and to a bone, where they start an infection. Bones that have been weakened or damaged, such as one that has been injured recently, are more susceptible to bacterial invasion.

Pyogenic spondylitis commonly arises from arterial spread of bacteria, usually through skin, respiratory tract, genitourinary tract, gastrointestinal tract or the oral cavity. The cellular bone marrow with voluminous languid spinal blood supply makes it particularly vulnerable to bacterial infection.

In lab tests, C‑reactive protein (CRP) is elevated in 90% or more of patients with spinal infection providing more specificity than erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). The variability in the source(s) of infection requires blood cultures, urinalysis, and urine for culture from patients suspected of having a spinal infection.

Figure 1. A. Vertebral buckle or fracture; B. Vertebral osteomyelitis or abscessed Schmorl’s node; C. Disc posterior herniation; D. Schmorl’s node with Hemangioma or osteoid osteoma; E. Disc protrusion with desiccation; F. Schmorl’s node; G. Vertebral osteomyelitis or wide Schmorl’s node

Kapasi AJ, et al. studied 59 articles published from 2010 through April 2015 to assess the diagnostic performance of over 112 unique host biomarkers in discriminating bacterial from non-bacterial infections. The most frequently evaluated host biomarkers identified in over five years of publications were CRP, WBC, PCT, neutrophil count, and IL-6. One of the best performing host biomarkers identified was HBP, albeit only in two studies.

Several of the high performing biomarkers were combinations of host biomarkers or combinations including protein biomarkers and gene-classifiers. While many of the identified host biomarkers are currently available in commercial assays (i.e. blood cell counts, ESR, CRP, PCT, calprotectin), most existing assays are not specifically designed to differentiate bacterial from non-bacterial infections.

Typical cutaneous infections involve inflammation, abscess, and pain. An infection within bone marrow has similar characteristics. Symptoms of osteomyelitis include deep pain and muscle spasms in the inflammation area, lethargy, and possible fever. Around 80 percent of cases develop because of an open wound.

Bone infection is not something that may be apparent on X-rays that are used to visualize non-liquid masses—though X-rays may be used to measure bone degradation. An MRI provides images of moist tissues. A skilled radiologist can adjust settings to help physicians visualize abnormal viscosity within bone matter. (Software for viewing digital radiology images also includes contrast adjustments.) The occasional presence of gas or fat-fluid levels in the bone marrow cavity is very specific for osteomyelitis outside of a context of trauma.

When pus collections have formed, they often are low in T1-weighted and high in T2-weighted signals. The earliest signs are blurring of the endplates and decrease in disc space, which happen two to eight weeks after the onset of the infection. After eight to 12 weeks, obvious bony destruction is observed.

Figure 2. Pyogenic spondylitis evident in sixty year-old female MRI with contrast.

Endplates are the edges of the discs between the bony vertebrae. These barriers contain the normally mucilaginous nucleous puloposus within each disc. A thining or compromised endplate allows the nucleous to leak into adjacent vertebrae under pressure.

The challenge for physcians is determining whether endplate degradation is the result of trauma, gradual age-specific deterioration, or disease. Additionally, it must be established whether the endplate breach causes inflammation, disc collapse, and possible weakening of the vertebral structure.

Moisture within a disc can decrease. This condition is called desiccation. The desiccated disc can leak remaining fluid or, with additional hardening, have the effect of piercing vertebrae. This abnormal adjoining of discs to vertebrae reduces mobility.

Distinguishing Bone infection From Cancerous Tumor

Distinguishing between hematogenous osteomyelitis and a bone tumor is difficult when there is no trauma, no known systemic disease, and no evident sign of local infection. An eight-year study of 244 patients by S. Shimose, et al. concluding in 2003 provides useful markers of distinction. (Table 1.)

Table 1. Histology-based diagnoses for 244 consecutive patients.

| Diagnosis | Patients | High CRP | High WBC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteomyelitis (15 pts) | Osteomyelitis | 15 | 9 | 3 |

| Malignant bone tumors (83 pts) | Osteosarcoma | 33 | 2 | 1 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 15 | 7 | 0 | |

| Chondrosarcoma | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | 8 | 2 | 2 | |

| Ewing’s sarcoma | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Malignant lymphoma | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| Others | 10 | 3 | 1 | |

| Benign bone tumors (77 pts) | Osteochondroma | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Giant cell tumor | 18 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chondroma | 14 | 1 | 0 | |

| Osteoid osteoma | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chondroblastoma | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Others | 10 | 1 | 0 | |

| Tumor-like lesions (69 pts) | Simple bone cyst | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| Fibrous dysplasia | 11 | 0 | 1 | |

| Aneurismal bone cyst | 7 | 1 | 0 | |

| Nonossifying fibroma | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Eosinophilic granuloma | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| Ganglion | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Others | 18 | 0 | 0 |

CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: white blood cell count

All patients experienced pain, with swelling in eight. Fever elevation was noted in only two subacute-stage patients. A high level of C‑reactive protein (CRP) was observed in nine patients, and white blood cell (WBC) count was high in three.

A high level of alkaline phosphatase over an age-appropriate level was not seen. Radiographs showed the central transparent zone of osteolysis with a well-marked outline in 12 patients and an additional osteosclerotic rim surrounding the zone in seven of these patients.

According to Krzysztof Siemionow, MD, et al., “Back pain is typically focal to the level of the lesion and may be associated with belt-like thoracic pain or radicular symptoms of pain or weakness in the legs. A spinal mass can cause neurologic signs or symptoms by directly compressing the spinal cord or nerve roots, mimicking disk herniation or stenosis.” Anything that grows on or near the spinal cord or brain stem can lead to “neuropathic” itch because the affected nervous system misfires.

Central osteosclerosis was seen in three chronic-stage patients. Periosteal reaction was seen in four chronic-stage patients and in one subacute-stage patient. MRI demonstrated the penumbra sign in six subacute-stage patients and five chronic-stage patients. The granulation tissue culture was positive in 11 patients: Staphylococcus aureus in eight, Salmonella in two, and Staphylococcus epidermidis in one.

Figure 4. The vertebral body and adjacent structures can be depicted as four disparate zones when considering surgery to treat vertebral body tumors.

The principal objectives of surgery include nerve root decompression, stabilization, and reconstruction of the anatomic spinal column. The surgical approach depends on the location of the tumor, the presence or absence of spinal instability, and the presence or absence of neural compression or neural deficit.

In 1989, James Weinstein proposed a model designed to enhance surgical planning in patients with spinal metastasis. In this model, the vertebral body is delineated into four zones, which are used to describe the location of the metastatic lesion. (Figure 4.)

Distinguishing Various Types of Vertebral Infection

After ruling out carcinoma, it is necessary to identify the source of infection. This is aided with assistance of a microbiologist or infectious disease specialist. Brucellosis, a zoonotic infection with worldwide distribution, is caused by small Gram-negative bacillifrom the genus Brucella.

In humans, brucellosis often is contracted by handling contaminated animal products or by consuming dairy products made from unpasteurized milk. The musculoskeletal system is most often affected, and the most common site of bone brucellosis is the spine. The diagnosis of brucellar spondylitis is not always easy but is very important to ensure proper treatment.

Aspergillus is a saprophytic fungus that may cause spinal infection within immunocompromised patients. It also occurs very rarely in immunocompetent patients—more so with a predisposed fungal allergy. Imaging for Aspergillus-induced spondylitis resemble those of pyogenic spondylitis.

A factor intrinsic to fungi that may contribute to the absence of signal hyperintensity in discs is the presence of paramagnetic and ferromagnetic elements within the fungi, a finding similar to the proposed mechanism for the signal hypointensity in fungal sinusitis on T2-weighted images. In addition, the nuclear cleft in Aspergillus-induced spondylitis may be preserved.

Awareness of the atypical imaging patterns of spinal infection is important to avoid delay in diagnosis. Atypical patterns include involvement of only one vertebral body, one vertebral body and one disc, and two vertebral bodies without the intervening disc. Although it is uncommon, involvement of an isolated vertebral body without the adjacent discs or involvement of one vertebral body and one disc may be seen on MRI with contrast.

It is necessary to be able to distinguish degenerative and inflammatory spinal diseases from infectious spondylitis. Conditions such as discogenic vertebral body degeneration in the inflammatory phase; acute cartilaginous node; ankylosing spondylitis; SAPHOsyndrome, which is a combination of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis; and neuropathic spine may lead to alterations in signal intensity that may be mistaken for infection.

Osteoid osteoma is a small, benign osteoblastic tumor consisting of a highly vascularized nidus of connective tissue surrounded by sclerotic bone. Three-quarters of osteoid osteomas are located in the long bones, and only 7-12% in the vertebral column. The classical clinical presentation of spinal osteoid osteoma is that of painful scoliosis. (Figure 2-D.)

Treatment Options for Vertebral Infection

Osteomyelitis is not limited to to vertebrae. It can be manifested in long bones within the legs, feet, arms, or other parts of the body. Treatment varies according to the source of infection. It is prudent to consider patient exposure to toxins. Was the condition precluded by a rash as possible entry point for the infection? Is the patient immunosuppressed? Does the patient have an allergy to specific molds? Thorough patient history leads to more rapid and accurate diagnosis.

Patients with osteomyelitis usually need to be hospitalized. They typically receive antibiotics for 4 to 6 weeks to combat the infection. Early spinal infections are sometimes treated with oral and/or intravenous antibiotics. Because infected bone often has a poor blood supply, oral antibiotics may be unable to effectively get to the infection via the bloodstream.

Absorbable antibiotic bead treatment for osteomyelitis is a surgical procedure used to implant beads that have been impregnated with calcium sulfate or calcium phosphate into infected bone.

Following debridement, the surgeon packs antibiotic beads into the opening. Antibiotics within the beads help kill the microorganisms causing the infection. The beads break down over time, facilitating new bone growth once the infection is gone.

Environmental toxic exposure must be eliminated to prevent reinfection following surgery. The references below provide more comprehensive diagnostic and treatment information with representative images. With severe vertebral degeneration, vertebroplasty may be warranted.

Enjoy more articles about orthopedics

ClinicalPosters offers human anatomy charts, scientific posters, and other services that compliment articles about orthopedics. Slide extra posters into DeuPair Frames without removing from the wall.

Show your support by leaving an encouraging comment to keep the research going.

Support the writing of useful articles about orthopedics by exploring human anatomy charts, scientific posters, and other products online. You may sponsor specific articles.

ClinicalPosters provides human anatomy charts, scientific posters, and other products that compliment useful articles about orthopedics.

ClinicalPosters offers human anatomy charts, scientific posters, and other products online.

You can sponsor useful articles about orthopedics or donate to further research.

References

- Pyogenic spondylitis. W. Y. Cheung and Keith D. K. Luk. nih.gov

- Osteomyelitis - Symptoms. Radiology Picture of The Day. nhs.uk

- Widdrington JD, Emmerson I, Cullinan M, et al. Pyogenic Spondylodiscitis: Risk Factors for Adverse Clinical Outcome in Routine Clinical Practice. Med Sci (Basel). 2018;6(4):96. Published 2018 Oct 30. doi:10.3390/medsci6040096

- Infectious Diseases in the Aging: A Clinical Handbook. Thomas Yoshikawa, Dean Norman

- Osteomyelitis Human Diseases and Conditions Forum. humanillnesses.com

- Osteomyelitis and Weight gain - unintentional - from FDA reports. ehealthme.com

- Host Biomarkers for Distinguishing Bacterial from Non-Bacterial Causes of Acute Febrile Illness: A Comprehensive Review Anokhi J. Kapasi, et al. plos.org

- Identifying serious causes of back pain: Cancer, infection, fracture. Krzysztof Siemionow, MD, et al., Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2008 August;75(8):557-566

- Differential Diagnosis between Osteomyelitis and Bone Tumors. S. Shimose, T. Sugita, T. Kubo, T. Matsuo, H. Nobuto & M. Ochi (2008) PDF. tandfonline.com

- Pitfalls in osteoarticular imaging: How to distinguish bone infection from tumour? T. Mosser, et al. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging, 2012-05-01, Volume 93, Issue 5, Pages 351-359. clinicalkey.com

- MR Imaging Assessment of the Spine: Infection or an Imitation? Sung Hwan Hong, MD, et al. rsna.org

- Surprising Reasons You're Itchy. webmd.com

- Metastatic Spinal Lesions: State-of-the-Art Treatment Options and Future Trends. B.A. Georgy. ajnr.org

- Radiological Imaging Findings of a Case with Vertebral Osteoid Osteoma Leading to Brachial Neuralgia. Erkan Gokce, et al. nih.gov

- Gogia JS, Meehan JP, Di Cesare PE, Jamali AA. Local antibiotic therapy in osteomyelitis. Semin Plast Surg. 2009;23(2):100-107. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1214162

- Antibiotic Beads. youtube.com

- Vertebral Hemangioma. radsource.us

- Figure 1 vertebrae illustration ©2017 Kevin R Williams

Romance & Health Intertwine. Fall in love with a captivating romance miniseries that explores the essence of well-being. Become a ClinicalNovellas member for heartwarming tales.

Romance & Health Intertwine. Fall in love with a captivating romance miniseries that explores the essence of well-being. Become a ClinicalNovellas member for heartwarming tales.